Pages

▼

12 Dec 2010

23 Oct 2010

Making paper. Part 2

These are some papers made in previous years.

These papers include bits of moss. I thought about sending some sheets of this to Kate Moss. The one on the right includes moss and onion skin. I thought about sending some sheets of this to Kate Moss for when she writes to someone who has upset her.

These papers have all sorts of bits of paper, grass, moss, reed, onion skin in them. The dark paper is made by including pulped black serviettes in the mix.

This paper has chopped reeds in it.

I typeset the names of all the characters in Shakespeare's plays, laser-printed them out on black paper and applied gold foil to them. I ripped the sheets of names into small pieces and incorporated them into the paper.

This was an experiment in which, in the winter of 2000, I went to Stratford-upon-Avon and shot photos of the river. My intention was to digitally adjust these images and print them using foil inks with a silver printed under the colours of the water.

In addition, I removed the black in the photos so that the colour and texture of a handmade paper would show through. The papermaking experiments were towards creating a paper made from, or including, reeds from the river Avon.

Other work came in and I left that project. The foil ink printer is still unused. I did, however, finish the images by using a scan of black handmade paper and printing the images without the silver underprint. They can be seen in the effervescence gallery at imagekind.com.

Making paper. Part 1

These papers include bits of moss. I thought about sending some sheets of this to Kate Moss. The one on the right includes moss and onion skin. I thought about sending some sheets of this to Kate Moss for when she writes to someone who has upset her.

These papers have all sorts of bits of paper, grass, moss, reed, onion skin in them. The dark paper is made by including pulped black serviettes in the mix.

This paper has chopped reeds in it.

I typeset the names of all the characters in Shakespeare's plays, laser-printed them out on black paper and applied gold foil to them. I ripped the sheets of names into small pieces and incorporated them into the paper.

This was an experiment in which, in the winter of 2000, I went to Stratford-upon-Avon and shot photos of the river. My intention was to digitally adjust these images and print them using foil inks with a silver printed under the colours of the water.

In addition, I removed the black in the photos so that the colour and texture of a handmade paper would show through. The papermaking experiments were towards creating a paper made from, or including, reeds from the river Avon.

Other work came in and I left that project. The foil ink printer is still unused. I did, however, finish the images by using a scan of black handmade paper and printing the images without the silver underprint. They can be seen in the effervescence gallery at imagekind.com.

Making paper. Part 1

22 Oct 2010

Making paper. Part 1

This is a very enjoyable, deeply satisfying, thing to do.

The satisfaction in it arises when you lift the mould out of the chaotic maelstrom of papermaking pieces and particles in the water. The water runs through the mesh and the particles settle flat, sucked down as the water runs through. All that chaos becomes a settled, fixed, unique creation.

Strictly, this is recycled paper. Rip up some ordinary paper into small squares. We used the sheets discarded from our inkjet printer over time. Cover with water and leave to soak overnight. Then run the soaked paper pieces through a blender to make a pulp.

Separately soak each of the other ingredients you will include in your paper. These might be: coloured paper, tissues, pictures or words on small pieces of paper, pieces of dried grass, dried leaves, whatever. (You may or may not wish to run these other ingredients through a blender; it depends how big you want them to be, and how much blended into the paper.)

Drop a few handfuls of the paper pulp into a tub of water along with any other ingredients you wish to appear in the finished paper. We used pieces torn from a colour magazine.

For this next stage you need a frame with gauze stretched over and fixed, called the mould, and a frame the same size with no gauze (this is called the deckle). You can buy these (here) or make your own mould and deckle using two empty picture frames.

Bought moulds and deckles: one mould fixed with gauze, the other with perforated zinc.

Stir up the pulp and water mixture. Holding the frame and deckle together, plunge them into the mixture and bring them up horizontal, letting the water run through, and leaving a layer of pulp on top of the gauze.

Lifting out the mould and deckle with a layer of pulp on it.

Lift off the deckle. Turn over the frame with the pulp on it and lay it on top of a wet cloth (we used J-cloths) - this is called the couching cloth.

Lifting off the deckle.

Laying the pulp and mould down on the cloths.

Press a little and lift slowly from one edge, leaving the pulp behind on top of the cloth. Cover this with another wet cloth ready for the next layer of pulp from the mould. Continue like this.

Lightly press the pulp onto the cloths.

Lift the mould away.

Press the pile of cloths and pulp layers to squeeze the water out.

We pressed the paper under a pile of bricks..

Remove the pile of cloths and paper pulp from the press and hang to dry.

Peel paper from cloth when dry.

Three sheets of finished paper.

Scented Herb Papers: How to Use Natural Scents and Colours in Hand-Made Recycled and Plant Papers.

Scented Herb Papers: How to Use Natural Scents and Colours in Hand-Made Recycled and Plant Papers.

This is a delightful papermaking book which, in addition to colour photos of everything and good simple papermaking instructions, tells you how to scent and colour your paper and make useful items from it. The methods described in the book are pretty much the same as we used in Making paper, Part 1, but with more detail given about each stage.

Making paper. Part 2

The satisfaction in it arises when you lift the mould out of the chaotic maelstrom of papermaking pieces and particles in the water. The water runs through the mesh and the particles settle flat, sucked down as the water runs through. All that chaos becomes a settled, fixed, unique creation.

Strictly, this is recycled paper. Rip up some ordinary paper into small squares. We used the sheets discarded from our inkjet printer over time. Cover with water and leave to soak overnight. Then run the soaked paper pieces through a blender to make a pulp.

Separately soak each of the other ingredients you will include in your paper. These might be: coloured paper, tissues, pictures or words on small pieces of paper, pieces of dried grass, dried leaves, whatever. (You may or may not wish to run these other ingredients through a blender; it depends how big you want them to be, and how much blended into the paper.)

Drop a few handfuls of the paper pulp into a tub of water along with any other ingredients you wish to appear in the finished paper. We used pieces torn from a colour magazine.

For this next stage you need a frame with gauze stretched over and fixed, called the mould, and a frame the same size with no gauze (this is called the deckle). You can buy these (here) or make your own mould and deckle using two empty picture frames.

Bought moulds and deckles: one mould fixed with gauze, the other with perforated zinc.

Stir up the pulp and water mixture. Holding the frame and deckle together, plunge them into the mixture and bring them up horizontal, letting the water run through, and leaving a layer of pulp on top of the gauze.

Lifting out the mould and deckle with a layer of pulp on it.

Lift off the deckle. Turn over the frame with the pulp on it and lay it on top of a wet cloth (we used J-cloths) - this is called the couching cloth.

Lifting off the deckle.

Laying the pulp and mould down on the cloths.

Press a little and lift slowly from one edge, leaving the pulp behind on top of the cloth. Cover this with another wet cloth ready for the next layer of pulp from the mould. Continue like this.

Lightly press the pulp onto the cloths.

Lift the mould away.

Press the pile of cloths and pulp layers to squeeze the water out.

We pressed the paper under a pile of bricks..

Remove the pile of cloths and paper pulp from the press and hang to dry.

Peel paper from cloth when dry.

Three sheets of finished paper.

This is a delightful papermaking book which, in addition to colour photos of everything and good simple papermaking instructions, tells you how to scent and colour your paper and make useful items from it. The methods described in the book are pretty much the same as we used in Making paper, Part 1, but with more detail given about each stage.

Making paper. Part 2

9 Oct 2010

Valerian

Two squirrels in the head disorder

As the physician states, valerian relaxes without the side effects of most drugs used to produce the same result. It won't make you feel drowsy or drugged. The muscles and the mind are just relaxed. There is a condition I call "two squirrels in the head disorder". One of its symptoms is that your mind starts racing nonstop from one stressful thought to the next when all you really want to do is fall asleep. It's like having two squirrels in your head chasing each other's tails.

Of course, this usually happens when you have something going on the next morning that is killer important, some sort of activity that required your being at your best. The more you can't sleep, the more you check the clock to see how much sleep you haven't had thus far. At this junction, if you hop out of bed and make yourself a cup of hot valerian tea, the squirrels will move on, and your mind will slow down enough for you to fall to sleep. If you are in the middle of a stressful period, three cups a day or one cup right before bedtime will help you through.

Herbalism can be confusing at first because many herbs have a range of beneficial ingredients, some of which can often be found in other herbs. But this book focuses on one common herb for each ailment, and gives an interesting discussion of it, with history, use and preparation.

Valerian flowers: The scent from valerian flowers is delightful, like a mild jasmine, and faintly musky. In the summer, as we walked past the plant, with its flowers at the top of eight-foot stalks, we wondered where the strangely pleasant smell was coming from.

Valerian flowers are said to be good for cutting and displaying in the house where they add their delightful scent.

Valerian root: This is the part of the plant used to make valerian tea.

Valerian root washed.

Valerian root dried.

Valerian hot chocolate

There's a delicious-sounding recipe for valerian hot chocolate in James Wong's Grow Your Own Drugs

.

To make 3 cups requires:

3 tbsp fresh valerian root

3 tbsp fresh lemon balm leaves

3 tsp fresh lavender leaves

6 leaves and 3 heads from fresh passion flowers

peel of 1.1/2 oranges

900 ml full-fat milk

50g dark chocolate (min 50% cocoa solids)

dash of vanilla extract

1. Chop the top and bottom from the fresh valerian root. Add the valerian, lemon balm, lavender, passion flowers, orange peel and milk to a pan and gently heat for 5-10 minutes. Strain.

2. Pour the infused milk back into the pan, then add the dark chocolate and vanilla extract and stir until melted. Drink at once.

3 Oct 2010

We are stardust

In 1957, Hoyle and Fowler showed that all the elements from which our world is made – from carbon atoms to uranium atoms – had been cooked inside stars eons ago from a basic fuel of hydrogen. These heavy elements were then blasted into space in great stellar explosions called supernovae, where they later congealed into planets, mountains – and humans. We are stardust, in other words. (Source)

Joni Mitchell:

We are stardustHere's a video of Joni Mitchell singing We Are Stardust at Woodstock, California, 1969.

We are golden

And we've got to get ourselves

Back to the garden.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[The unretouched photo of the full moon, above, taken on 24th July 2010, shows a green object which appears to be a planet. It is, I believe, just lens flare. (Click photo to enlarge)]

30 Sept 2010

Turnips

We had two packets of turnip seed in our collection, so we put them in to use them up.

Unfortunately, they're not very popular here: we tried them boiled and roasted, but they still didn't justify their place in the garden.

Yet, before now, I've bought a pound of small ones and eaten them like apples, and enjoyed them. But the ones we've grown now have a bit too much of that radish heat about them.

All's not lost, though. It happened that a duck left six ducklings behind (story here), and they have enjoyed the turnips, the tops particularly.

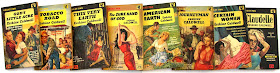

I think my urge to eat them like apples and to grow them was probably romantic. For many years now I have enjoyed the novels of Erskine Caldwell (the cheap-looking paperbacks you used to see on second-hand bookstalls).

In Tobacco Road , he writes of Jeeter Lester, the father in a poor family of sharecroppers in the US south of the 30s, and his enjoyment of raw turnips.

, he writes of Jeeter Lester, the father in a poor family of sharecroppers in the US south of the 30s, and his enjoyment of raw turnips.

A hungry Jeeter is trying to con a visitor to the house out of his sack of turnips:

Caldwell's biographer writes that Erskine's father, a minister, was described to the son by his mother as "'a noble warrior of the truth' - a man who stood up against the small-mindedness, bigotry and cruelty he found in the small towns of his native region. As an adult, Erskine would make his father's causes his own, and in his writing he sought to honour and vindicate him.")

writes that Erskine's father, a minister, was described to the son by his mother as "'a noble warrior of the truth' - a man who stood up against the small-mindedness, bigotry and cruelty he found in the small towns of his native region. As an adult, Erskine would make his father's causes his own, and in his writing he sought to honour and vindicate him.")

Unfortunately, they're not very popular here: we tried them boiled and roasted, but they still didn't justify their place in the garden.

Yet, before now, I've bought a pound of small ones and eaten them like apples, and enjoyed them. But the ones we've grown now have a bit too much of that radish heat about them.

All's not lost, though. It happened that a duck left six ducklings behind (story here), and they have enjoyed the turnips, the tops particularly.

I think my urge to eat them like apples and to grow them was probably romantic. For many years now I have enjoyed the novels of Erskine Caldwell (the cheap-looking paperbacks you used to see on second-hand bookstalls).

In Tobacco Road

A hungry Jeeter is trying to con a visitor to the house out of his sack of turnips:

"I got a powerful gnawing in my belly for turnips. I reckon I like winter turnips just about as bad as a nigger likes watermelons. I can't see no difference between the two ways. Turnips is about the best eating I know about."(Anyone feeling that Caldwell's use of the word 'nigger' is derogatory should understand that he uses the speech of the people of that day. Caldwell himself was against discrimination and denigration of all poor, black and white, and many Southerners reviled him for his brutal exposés of their region.

Caldwell's biographer

29 Sept 2010

Fruit leather

Damson, apple, grape and fennel fruit leather.

This year, instead of simply drying the damsons as we did last year (see here), we made fruit leather - from damsons and from various combinations.

To make fruit leather, remove all stones, peel and core apples, then put the fruit into a blender and blend until it's as fine as you want it. Pour out onto an oven tray covered with clingfilm a 1/8" to 1/4" layer of the fruit pulp. (Be sure that all stones are removed. If you leave one it will be chopped in the blender into hard, sharp little pieces.)

Place in an oven on very low, about plate-warming temperature, and leave for 24 hours. Peel the drying pulp off the clingfilm and turn it over. Leave for another 12 hours.

Roll it up in the clingfilm and store in the fridge or freezer -

Varying the ingredients -

Apple, banana, honey and toasted oats.

Damson and liquorice, poured after blending soft liquorice and damsons.

Damson and liquorice dried.

Damson and liquorice cut with scissors into strips for eating.

There's more info on fruit leathers and a table of the suitability of various fruits here.

This year, instead of simply drying the damsons as we did last year (see here), we made fruit leather - from damsons and from various combinations.

To make fruit leather, remove all stones, peel and core apples, then put the fruit into a blender and blend until it's as fine as you want it. Pour out onto an oven tray covered with clingfilm a 1/8" to 1/4" layer of the fruit pulp. (Be sure that all stones are removed. If you leave one it will be chopped in the blender into hard, sharp little pieces.)

Place in an oven on very low, about plate-warming temperature, and leave for 24 hours. Peel the drying pulp off the clingfilm and turn it over. Leave for another 12 hours.

Roll it up in the clingfilm and store in the fridge or freezer -

Varying the ingredients -

Apple, banana, honey and toasted oats.

Damson and liquorice, poured after blending soft liquorice and damsons.

Damson and liquorice dried.

Damson and liquorice cut with scissors into strips for eating.

There's more info on fruit leathers and a table of the suitability of various fruits here.

28 Sept 2010

Garlic in goose fat

We had a good crop of garlic this year, from which we made garlic in goose fat.

This is simply peeled garlic cloves simmered until soft in goose fat.

The cooked cloves are taken out of the fat and placed in a jar, with goose fat added to cover them.

Great winter food, spread on toast, with a sprinkle of salt.

This is simply peeled garlic cloves simmered until soft in goose fat.

The cooked cloves are taken out of the fat and placed in a jar, with goose fat added to cover them.

Great winter food, spread on toast, with a sprinkle of salt.

19 Sept 2010

3 Sept 2010

Making an earth oven. Part 3

Lime plaster finish

At last, some sunny weather and a chance to put the lime plaster finish on the oven.

As mentioned in the previous section, lime plaster is the preferred finish to the oven, because it breathes. We searched the internet for information on lime plaster mixes and ended with too much data and too many formulae.

Many different mixes are given, from 1:2, lime to sand, to 1:9. There are accounts of the Romans and their addition of 'pozzolan' to produce a lime mortar mix which has lasted 2,000 years. Pozzolan is volcanic ash. Apparently, brick dust will do a similar job, and cement will too. I read of the addition of chopped hair, animal hair, human hair is too fine, to the lime plaster mix, and of chopped straw.

In the end we made our own mix, starting with a bag of lime mortar dry ready-mix of 1 to 2.1/2, lime to sand, bought online from Masons Mortar. We added about another 1.1/2 of coarse sand; about 1/8th of wood ash, the same of chopped straw, and of cement. This mix was put on about 1" thick.

Why lime?

Making an earth oven. Part 1

Making an earth oven. Part 2

See all Parts.

At last, some sunny weather and a chance to put the lime plaster finish on the oven.

As mentioned in the previous section, lime plaster is the preferred finish to the oven, because it breathes. We searched the internet for information on lime plaster mixes and ended with too much data and too many formulae.

Many different mixes are given, from 1:2, lime to sand, to 1:9. There are accounts of the Romans and their addition of 'pozzolan' to produce a lime mortar mix which has lasted 2,000 years. Pozzolan is volcanic ash. Apparently, brick dust will do a similar job, and cement will too. I read of the addition of chopped hair, animal hair, human hair is too fine, to the lime plaster mix, and of chopped straw.

In the end we made our own mix, starting with a bag of lime mortar dry ready-mix of 1 to 2.1/2, lime to sand, bought online from Masons Mortar. We added about another 1.1/2 of coarse sand; about 1/8th of wood ash, the same of chopped straw, and of cement. This mix was put on about 1" thick.

Why lime?

from The Lime Plastering Company's site:

Lime delivers its hardness and its waterproofing qualities through a process called carbonation. The raw lime mortar sits wet on the wall for several days while it absorbs carbon from the abundant atmospheric CO2 and the curing process begins from the outside inwards. In three or four days the outer surface will be hard to the touch and in ten you will need a chisel to scratch it. Over the next weeks and months the lime will gradually continue this bonding and binding process to form a tough water repellent surface, converting this atmospheric carbon to seal to a fine, flexible finish of ninety-five percent pure calcium carbonate and in the process it will have removed a good portion of CO2 from the surroundings. The longer this process continues, the harder and deeper the set becomes, reaching a micro-porous finish that permits the outflow of moisture by evaporation from within the walls, while preventing the larger molecules of liquid rain from penetrating the structure.

As the lime cures and maybe in later years also, you may find, under close inspection, that tiny cracks have appeared in your lime mortar or render, but these cracks belong to the life cycle of a lime build and though you may not immediately see it, the carbonation process is continuing, for wherever 'new' lime is exposed, ie; in weather cracks or other damage, the lime simply takes in more CO2 from the air around and seals the wound by exactly the same process through which it set hard in the first place.

Making an earth oven. Part 1

Making an earth oven. Part 2

See all Parts.

byWong](http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?MarketPlace=US&ServiceVersion=20070822&ID=AsinImage&WS=1&Format=_SL160_&ASIN=B003ZTPP3A&tag=pheasa-20)